Portuguese martial arts: "Jogo do Pau", the art of Portuguese stick fencing.

Probably the most famed Portuguese martial art is jogo do pau (literally "stick game", also known in Portugal as jogar as canas, "playing/casting the reeds/canes" or combate a/jogo de varapau, "combat by beanbagpole/beanbagpole game"), a form of stick fencing shared by Portugal and the northern neighbouring and related Spanish region of Galicia/Galiza (especially common in the areas around the borderlands and Galician Minho/Miño river, to the point that Galician Xanquin Lorenzo Fernandez proposed a Portuguese origin to its presence in Galician borderlands). It is not exactly known when or how it started, nor how old it is. Like many similar stick fighting arts, it mostly came from peasants practicing and fighting (mostly raiders/invaders or to settle small quarrels) with farming tools or easily made clubs and (quarter)staffs out of tree branches they could find all around them in the countryside and woods, and country gents practicing sword fights with less lethal and harming training weapons, similar to samurai practicing with kendo wooden swords or the Tamils fighting for sport or harmful intent with staffs doing silambam. Those root causes of its origin standing, its origin could be late medieval (King Ferdinand/Fernando created on September 12, 1383 the first Lisbon police corp, the Quadrilheiros/Posse-member with 8 feet/1.76 meters and a green rod with the shield and besants Portuguese royal arms, and as shown in an illuminated illustration from Jean Wavrin's Recueil des Croniques et Anchiennes Istories de la Grant Bretaigne, à présent nommé Engleterre/"Collection of the Chronicles and Ancient Histories of Great Britain, at present named England" it was a common weapon in the Portuguese army in the 1385 Aljubarrota battle in the Western Region), earlier in the Middle Ages (it seems during the Christian reconquest, staffs were carried and used as weapons by people on foot like the legendary Friar Hermígio "Basto Eu/Me I'll do" Romarigues from Lands of Basto, and even on horse, and ordálios, trials by combat, were fought by peasants with beanbagpoles until the Catholic Church started supressing them), Roman or even pre-Roman. There is only clear named reference to it by the 18th century. But some early roots of its fighting style and techniques can be found in an unexpected and royal source.

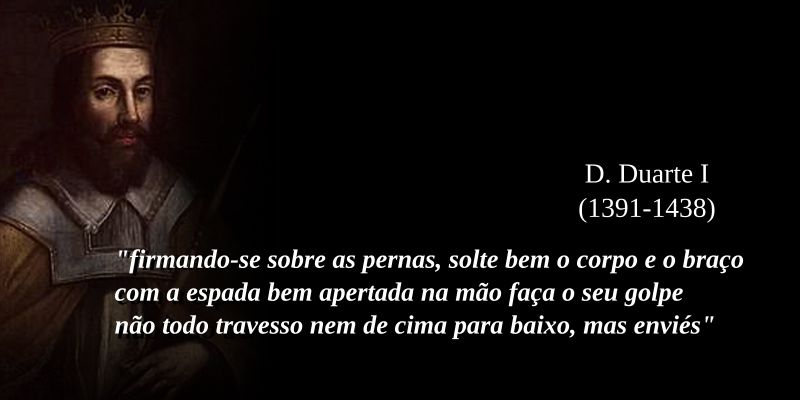

King Don Duarte (named after his maternal great-grand-father Edward III of England, since Duardos or Duarte are archaic/portuguesefied versions of Edward/Eduardo), «the Eloquent» or «the Philosopher-King», is more known (due to a mere 5 year reign, till he died of plague, started when he was already 42 years of age) as a brainy lawmaker and man of letters who allowed his brother the governor of the Order of Christ Infante Don Henry, «The Navigator» organise and finance sailings (not conquests) of the southern Moroccan and saharan shores, and whose armies failed to conquer Tangier and after January 1438 Leiria Cortes (King's Court) where he only heard and did not speak to finally decide not to surrender the praça (outpost) of Ceuta in exchange for his Tangier-captured brother Ferdinand/Fernando, and his books O Leal Conselheiro ("The Loyal Counsellor") as a guide of moral rulling with the first pages on the topic of the Portuguese longing feeling of missing saudade and Livro da Ensinança de Bem Cavalgar (literally "The Art of Riding on Every Saddle", translated (with some liberties) into English as The Royal Book of Jousting, Horsemanship, & Knightly Combat) at first seems to just follow in the footsteps of his father John/João I's Livro da Montaria ("Book of Venery") as a guide on a popular noble activity, giving since then the image of bookish, detatched and "flabby", in one word "unphysical", king; but upclose and personal, Edward was (as his chronicler Rui de Pina points out) a practical and nature-close man of the Renaissance and Age of Discoveries, practicing enthusiast of hunting, fencing, jousting and luyta (modern Portuguese luta, which is to mean "wrestling"). So Edward is more correctly a Miyamoto-Musashi-style figure, a thinking man's knightly warrior who also wrote down rules of his type of fighting and its underlining philosophy.

The Royal Book of Jousting, Horsemanship, & Knightly Combat is not just the possible first European horse-riding manual, but a manual on all sorts of activities that can be done on a horse, including fighting on horse (and practicing for it on foot) using swords or sticks (and using sticks to steer or calm horses while ridden). Due to this, his fighting tips (which are detailed enough that the on-horse focus from an earlier sentence is almost forgotten in many following sentences) with those weapons have been considered by the father/son jogo do pau promotor/practicioner duo of Antonio Franco Preto and Luis Preto as early descriptions of jogo do pau (which is probably why Portuguese stick fighting comes out so similar to the two-handed swordplay Montante technique and armoured Medieval fighting Béhourd European martial arts), and Edward (since it was his book to put whatever he wished on it) even dedicated a few pages to luyta (whose described techniques are quite close to another Portuguese martial art that we shall cover later, the Trahs-os-Montes and Beiras galhofa).

All his standing, the presentation by scholar and writer Candido de Figueiredo of a man with a staff defending himself from 2 knifed assailants in the 1st Vasco da Gama journey with jogo do pau techniques may be historically accurate even if not fully documentally confirmed. So he details lance/baton/spear techniques on the chapter II of section 1 of the book, chapter V of section 2, chapter II of section 4, chapter V, chapter VI, chapter X and chapter XIII of section 5, and chapter I of section 6, and sword techniques in the chapter VIII, XIX and XXI of section 1, chapter II, III and XIV of section 5. We shall go through all such passages.

Chapter II of section 1:

«In peaceful times those who are skilled horsemen have great advantage in jousts, in tournaments, playing with canes [emphasis mine], maneuvering and throwing spears. They hold the same advantage in all other dexterities performed in the course of riding that occurs frequently on the lords' estates. In those activities, since they have had the experience to overcome difficulties and troubles, the fact that they are skilled horsemen gives them advantages over others who face the same difficulties and troubles and have identical physical qualities, but do not have the same riding skills.

And to be very good at hunting up and down slopes, riding skills give them great advantages as they have the knowledge essential better to cope with collisions, to stay well poised on the horse and strong in the saddles enabling them better to strike with a weapon, as they know the limits their horses can endure and how to use them, simultaneously protecting themselves from many dangers. All these and other things that are going to be described in the THIRD PART are very much necessary to those who want to become good hunters. The lords greatly esteem those who are skilled horsemen and therefore have some basic qualities that are important in war and other activities; it is also very important to the lords to have on their estates many good horses and skilled horsemen able to ride them well.

It is also important for those who want to take employment for wages to show everywhere that they are knowledgeable in the equestrian arts, and be recognized as men able to perform important duties and to be trustworthy.»

Chapter VIII of section 1:

«I can also be thrown off to any of the four directions due to a collision or attack, or maneuvering or throwing a spear, or striking with a sword, or due to any other movement that I have not mastered well enough to avoid falling down as a consequence of my body movements and through my own fault, without having any reason to put the blame on the beast.»

Chapter XIX of section 1:

«Coming back to our main subject: there are some who get so excited about doing specific actions (like handling and throwing a spear) that, due to impatience and ignorance, they forget how they should behave to stay mounted, and fall off the beast. I have seen a few falling down for exactly that reason; they grasp the spear so strongly that they are unable to handle it for a long time and when they are physically forced to let it fall down to the ground, they also go down, keeping it company; others throw the spear with so much energy that they get unbalanced and follow it out of the saddle! Similar situations might happen when striking with a sword or doing any other thing; for lack of the necessary skills, many get unbalanced and fall down from the beast.»

Chapter XXI of section 1:

«As an example, whenever he is handling' a spear, he should be more concerned with staying firm on the saddle and keeping his legs pressed against the beast's body rather than with the strength and resistance of his hand and arm to handle the spear. And when he is not able to keep the spear in his hand anymore, he should drop it, not attempting to do more than he can; because he must-above all-keep himself firm and safe on the saddle. And having this in mind, he should then use his hand, his arm and his body to correctly handle and throw the spear.

And this is the way we should behave when we are mounted and want to do specific things, like striking with a spear or with a sword; we should never get ourselves unbalanced due to our body movements.

And if we are used to acting this way, it would become natural. And this is a good advice, very useful and beautiful to those who know how to do it.»

Chapter V of section 2:

«And he should learn to be strongly mounted on every type of saddle, to go over difficult ground— up and down hill— and to learn how to maneuver and throw a spear; and he should start learning the maneuvering of a spear using a lightweight one, because it is easier to learn the correct arm and body movements that way. And when they start learning how to maneuver a spear we should choose one without sharp ends to avoid any disaster; they can use pointless canes or wooden sticks with a weight in accordance with their strength enabling them to learn the art of maneuvering and throwing a spear without danger.»

Chapter II of section 4:

«If we are maneuvering or throwing a spear or doing any other thing, we should keep our upper body quiet and firm ensuring that — whatever the beast tries to do — we can always stay in control using the spurs and the hands (for the spear or the reins), showing no signs of embarrassment and an attitude as quiet as if we were riding leisurely or just walking around.»

Chapter 2 of section 5:

«In my opinion, there are more who are unable to be knowledgeable and skilled in a specific art or activity' due to their lack of a strong will than the ones who cannot achieve it just due to their physical limitations; nevertheless, I concede that there are some who, by nature, do excel in riding whereas there are others so limited physically that only through a lot of hard work are able to feel at ease when mounted on a beast. But, besides all these things related to nature, there are four main factors only related to the teachings aspects of riding which concern the ability to be at ease when mounted on a beast:

1. How to use and move the right arm to maneuver and throw a spear, to strike with a sword or to perform any other thing.

2. How to use and move the left hand and aim to hold and control the reins as necessary.

3. How to position and keep the legs and the knees when mounted and how and when to use the spurs.

4. How to have the proper attitude and countenance of the face and the body as described by me in the chapter about safety.»

Chapter III of section 5:

«You should train yourself fully armed and wearing your armour (as if you were going to war) and you should participate in jousts and tournaments, having with you good teachers to provide you with all the necessary counselling and warnings, before and after the action.

And it is essential, of course, to believe in and to follow to the letter the instructions and corrective actions you are to receive from them.

Acting similarly you will be able to be at ease when performing several other activities also important when you are mounted on a beast such as galloping up and down hill, hunting, maneuvering and throwing spears and playing with canes and striking with a sword. All these activities should be practiced by all those who want to be at ease when mounted on a beast as it is a known fact that a good and frequent practice is the best of teachers, without which nobody could acquire the necessary skills; and after having achieved that objective it is mandatory to keep practicing, otherwise the skills will be very quickly forgotten.

And nobody should feel embarrassed to carry swords at all times, even considering that many, never (or almost never) are going to take any advantage of the decision; even so, they carry them just because they think that sooner or later they might need to use them; their hearts feel light and merry knowing that their owners are skilled in many valuable and good arts, therefore they would have great advantage over others; it is a fact that many have successfully use their various skills in situations of great need and due to that ability are very much respected and highly regarded by all.»

Chapter V of section 5:

«Training should be done at first with the student standing on his feet (not mounted) and quiet and all the instructions should be exemplified using a light weight spear or a wooden stick, as it is easier to ensure that the correct actions are performed if we are maneuvering a light weight spear. The main instructions to achieve a correct maneuvering of a spear are the following:

At first, how to hold the spear in its most frequent initial position, vertical, near to our leg; we should have it firmly held in our hand with our arm stretched down.

As I just said the student should start learning to maneuver a light weight spear and its size and weight should be progressively increased until the maximum weight the student can correctly maneuver is defined.

Nobody should attempt to use spears weighting more than what he is physically capable of handling as it can produce such consequences as hernias, pain in the back, head, legs and hands without any benefit.

And as soon you have learned to maneuver a spear while not mounted on the beast, you should start trying it mounted, going around slowly to prove to yourself you can do it and also to enable your teacher to correct you whenever necessary and appropriate. And this is of the utmost importance because nobody is able to achieve the right attitude and act correctly in the art ot riding if he is not taught and corrected from the beginning. And the rider should progressively increase the beast's pace until he feels at ease in a strong gallop; then he will understand the great advantage he holds over others who are unable to match his skills.

Due to the great weight of the spear, the first step is to take it out of its vertical position and this should be done with a violent thrust of your arm and hand, raising the spear onto your breast; this being done, your hand should immediately glide along the spear's shaft, stretching your arm and enabling you to sustain the spear's weight for a while; then, you move your hand in the direction of your arm (though, to the back) and encase the spear’s butt in the restre [metal plate giving support to the lance] be also aware that you should hold the spear in the palm of your hand with your fingers firmly around it and not just with your fingers because, if you do that, the spear will probably slip out of them due to its great weight.

If you do not use a real restre you can use your armpit as an alternative when the spear is kept well balanced due to three support points, namely your armpit (with your arm tightly connected to your upper body), the lateral part of your breast (against which the spear's shaft is positioned) and your hand. And this way you have the spear under your control (and in a horizontal position, if that is your objective), firmly squeezed between your chest and your arm; and you should keep your body erect and act as elegantly as possible. And if you want to move the spear from its initial vertical position onto your lap you should also do it with a violent thrust of your arm and pull of your hand; but you should not forget immediately after that to put your arm in the correct position it should be whenever you are carrying the spear on your lap (as I said before). If you have an arondella [guard-piece firmly fixed to the spear's shaft to protect the rider's hand] fixed in your spear's shaft, be aware of its relative position; if it is near your lap, it is not only ugly but you can also hurt yourself if are not wearing your body armour.

(...)

If your spear has a gozete [attachment to the spear to help the handler hold and handle it] put your hand or at least one of your fingers over it, either if you are riding with or without a restre (it is easier to maneuver the spear if you have both— the restre and the gozete).

Do not forget to start maneuvering the spear from its initial vertical position using a violent thrust of your arm and pulling with your hand to raise the spear on to your breast; one additional warning on this subject: use your elbow to help support the spear until you are able to encase it in the restre and use the strength of your hand to keep the spear from falling down suddenly rather, raise the sharp end of the spear more than the required height and then allow' it to go slow'ly down to the correct position. (...)

If you carry' the spear de soo-braço [archaic Portuguese for sobre-braço/over-arm], you should have it strongly grasped in your hand and do not allow its sharp end to fall down.

If you are (...) against the wind, you should not carry the spear with its sharp end too high; you should also keep the spear tightly squeezed against your own body, holding it still and you should put — as soon as possible — the spear in the right position and direction for the collision.

(...)

And I am going to repeat some of my reasons — and to mention some more — to ensure that they are better understood; this is because I consider that it is more important to be sure that everything is well understood than to produce a very elegant text.

If you are maneuvering the spear with your hand close to its sharp end and are not using a restre, and want to move your spear to its position at the leg, you should squeeze the spear's shaft between the lateral part of your breast and your arm.

If you are using a restre, press the spear's shaft with your arm and elbow, encase it in the restre and do not forget to use your hand to keep the spear's sharp end from falling down under a certain height.

There are some who say that it is better to carry the spear resting on the left arm; they say that they put it in striking position quicker and also that they strike better to their left and to their back.

When the spear is carried on the right shoulder, some allow it to fall down over the right arm as a way of being able to protect their back quicker; others allow the spear's sharp end to fall down to the ground and recover it back to their shoulder for further maneuvers.

All these ways of maneuvering a spear are very useful to know as they could be used in times of need; those who know them all are riding more at ease than the others.

But I am not going to write about things I consider with no interest — such as maneuvering two or three spears simultaneously or handling them above the head; even so, I consider that those who do such things, feel and are at ease.

In summary (and in which concerns the carrying of the spear de soo-braço) the following errors can be made, namely:

• Carrying a spear that is too heavy, though you are unable to maneuver it correctly and may even fall down with it

• Leaning the body too much to the right

• Not being quiet (...) (feet, legs, head, body, spear)

• Carrying the spear at too much of an angle, or pointing too much to the outside or too high or too low

• Positioning the head and the (...) face too close to the spear

• Positioning the (...) head too high and leaning to the back

And to do everything right, the rider just needs to avoid all these errors.

(...) In our jousts there are riders who prefer to maneuver the spear using the left hand. About this I say that everyone should have his own specific techniques; if a technique is well practised, the hand, the arm and the body get used to it and eventually master it with the necessary good results. Let us consider as examples a string instrument player who is used to play using the fingers of one of his hands and a bird-hunter who favors one hand; they are both unable to do it correctly with the other hand (even knowing how it should be done).

Therefore we can see the importance for everyone of us to know how to use our own body to master any specific art or technique; we need not only to get the necessary knowledge how one thing should be done but we have to practice it at length (which is the only way to master it).

Final Advice and Considerations

There is one important piece of advice to be considered whenever we are maneuvering a big and heavy spear and we are not wearing our body armour; and I give this advice because that's what I always do in those circumstances:

• When I raise the spear from its initial vertical position, I allow my hand to glide for a while along the spear's shaft and with this technique the impact of the spear's weight when it falls down on my shoulder is reduced. Acting this way, I am able to stay quieter and at ease on the saddle and I think that this technique might be a big advantage for those who learn well how to use it.

• There are those who — even knowing how to maneuver a spear — feel embarrassed when doing it, either because their armour is not of good quality and does not fit them as it should, or the restre or the braçal [braço/arm protective armour] disturbs them, or they did not ensure that all the horse's harness— namely the interlaced ropes tying the stirrups underneath the horses belly — were properly prepared and fixed. Though, it is absolutely necessary that, before they start to participate in jousts, they train as many times as they need, until they feel at ease. For example, they should train several times to encase the spear's butt in the restre until they are sure they can do it correctly without feeling disturbed or embarrassed. And after several days of training they should also do it wearing their full body armour under conditions similar to the ones they are going to face in the future; and every single detail should be taken care of, including training to maneuver the spear to its final position, charging to the collision. (Details about the moment of collision are the objective of the next chapter.)

And those who decide to train not wearing their full body armour, should pay attention to every detail that might embarrass or disturb them in action, such as the clothes they wear— namely the doublet's sleeves (too tight or too loose)— which might cause them difficulties to correctly position their spear de soo-braço.»

Chapter VI of section 5:

«I am going to write down instructions I consider good and reasonable to enable all riders to act as they should at the moment of collision (in jousts and when hunting) and I hope that they would be taken into consideration by all those who want to avoid making the most common errors. In this chapter I am going to address the jousts— because they are the more important of the two situations.

Men are not acting as they should at the moment of collision, due to four main reasons:

Poor sighting, incorrect maneuvering of the spear, problems related to their horses and lack of a safe and strong will.

The first two reasons are to be discussed during this chapter (...); the fourth, is the objective of chapter(...) X (...).

Poor sighting

Some make mistakes because they close their eyes at the moment of collision, without even realising it! Others are aware of it but they are unable to avoid it. Others, because they have the helmet or the shield wrongly placed, are unable to see the other jouster at the moment of collision due to the (...) jolting movements even at a steady gallop.

There are those who - in the attempt to see the other jouster - move their eyes inside their heads and their heads inside their helmets, but in most cases that is not enough; in order to see— again — the other jouster, they also need to rotate their upper body by the waist, before the collision happens. The best way for a jouster to fix all these possible errors is to have with him a spotter knowledgeable in this art who, after each collision happens, starts asking the jouster why he thinks he succeeded or failed. Actually, it frequently happens that— especially if there was a violent collision — the jouster doesn't know what really happened and the spotter must be able to tell the jouster that he was not looking at his opponent at the moment of collision and should force him to correct this major error.

Nevertheless, when the jouster really has closed his eyes without realising it, it is more difficult to correct and the spotter should be allowed (and entitled) to tell the jouster in a very plain-spoken way not only that error but also all the other errors he identified; the jouster, feeling angry and annoyed with himself would then have the proper incentive he needs to correct himself.

As an example, if he has failed two or three times because he aimed the spear in the other jouster's direction too late, he should be told to do it earlier during the final run; actually, it might happen that, even not seeing the other jouster as he should, he might be lucky and his spear might find the adversary just because he had enough time to change the spear's direction; the pleasure of having making contact with the adversary once, might be enough to give the jouster the necessary strong will to keep his eyes well open!

A jouster might also lose sight of his adversary due to a wrong preparation of his body armour; one possible way of correcting this error is the following:

Being already mounted wearing your full body armour, put the spear de soo-braço and ensure the proper fitting of the helmet and the shield doing the following: keep the spear correctly positioned for the collision and even considering the eventual movements of the helmet and the shield due to the normal jolting at the gallop ensure that— up to the moment of collision— you always see half (or at least the last third) of your spear. If you cannot achieve that objective immediately, you should train it as many times as needed because you have to be able to do it; it is a fact that, one who cannot see properly, cannot be in the best possible condition at the moment of collision!

To ensure the correct position of the helmet and the best possible eyesight through it, it is in my' opinion better to fix it first in the back and only then in the front; acting this way, the helmet stays better fixed and it is better for your eyesight than to do the contrary.

To ensure the best possible view of your adversary at the moment of collision, you should have your body positioned directly facing him throughout all your run along the tilt barrier [tea in archaic Portuguese and tei in modern Portuguese, the barrier separating the joust field from spectators and the one separating both jousters] and right before the collision you should turn y'our head also directly to him, to see him face-to-face through the helmet, and not obliquely. This is the way to have the best possible sight of your adversary' at the moment of collision

Wrong maneuver of the spear

(...)

• First — Bad quality of the body armour — namely of the braçal — or bad preparation and placement of the restre, the shield, the arondella or the gozete.

• Second — The spear is too heavy.

• Third — The jouster is not quiet and at ease (...).

Let's address each one of them (looking for the solution):

First— The solution is obtained through training and rehearsals — as many times as needed — until the jouster can ensure that he is not going to be embarrassed by any piece of his armour during the joust. And before going to the tea to start the final run, put your spear two or three times de soo-braço to ensure that everything is at it should and that you feel yourself at ease.

Second — The jouster should ensure that he is not using a spear too heavy (in accordance with his own strength).

Third — Quietness and easiness are obtained through practice and knowledge of the art (...), as I said before. (...)

After all these things are ensured, the jousters should feel themselves at ease, calm and in control of their horses and their spears.»

Chapter X of section 5:

«(...) those who make mistakes due to too much haste and do not spend enough time in the proper preparation of their bodies and spears, fall under the scope of the second will which I named spiritual. As an example, that situation might happen with the crossbowmen who do not spend enough time preparing their crossbows and do not make the correct shots; as a result, the arrows go off in every possible direction.

And some of them, even having the understanding of their mistakes, are unable to correct them.

(...)

And the jouster should also consider the relative low level of the dangers involved in the jousts when compared with the dangers involved in doing other things such as throwing canes, hunting up and down hills and in wrestling, which are activities that most men practice without feeling fear; so, men should have the same willingness whenever they are jousting and they should also think that it is preferable to occasionally lose and fall off the horse than to miss or avoid the collision when jousting. And if they keep the necessary strong will and practice, they will not miss the collision.

Addressing now the second reason referred at the beginning of the chapter, there are three ways the jousters could use to avoid the mistakes already described:

1. The jouster should feel himself firm and at ease and carry the spear quietly and in the right direction; as soon he achieves that, he should force himself not to make any change until the collision happens.

2. A few moments before the collision, the jouster should squeeze the arm against his body and keep it firm, using all his strength; if he acts as described, he will not be able to make any additional change until the collision happens.

3. Those who are not able to do as described by any of these two ways (which are the best ones) should do the following: carry the spear slightly out of the way, tense the body just at the moment of collision and simultaneously bring the spear to the collision target. This option should be used by those who know that, whenever they squeeze the arm against the body, they are unable to avoid a change of direction of the spear they are carrying; that’s the reason why they cannot use anyone of the first two ways described.

I am going now to address the fourth reason referred at the beginning of the chapter: those who, being in advantage, make mistakes. They should not overlook a careful evaluation of his opponent and the preparation of his horse and spear; only then they should joust. One point should be considered by those who know they have the advantage in a joust: they should not be afraid to carry their shields slightly below their normal position; in my opinion, those who never take chances — from time to time— are not going to become good jousters.

Besides everything I have already written, there are two additional pieces of advice that should be taken into consideration:

1. If your opponent is still a bit far away and you are already carrying your spear de soo-braço, keep it a bit lower than the point you want to hit at the collision and raise it only in the last second. This is a good advice/option for two reasons: (1) you see your target much better and (2) you do not allow your spear to hit your opponent below the target point you have chosen (which could happen if you carry your spear the other way around — too higher that the target point, lowering it too much at the collision).

2. The two main aspects that help you to succeed at the moment of collision are: keep your eyes on your opponent all the time and maintain your body and will very strong up to the moment you see the ruquetes [3 or 4 embedded small spikes on the round flat surface of the tip of a Portuguese jousting spear/lance, replacing the usual European jousting spear/lance's pointed steel head, called rochets or coronets for the crown-like shape of it in French and English and rockets in English alone; this greatly reduced the physical danger for the jousters] of your spear hitting the target point you have chosen.»

Chapter XIII of section 5:

«The heavy spears require you to have your arm and shoulder loose and relaxed at the throwing moment. The light spears and the canes require you to throw the spear with a sudden movement centered in the middle of your arm.

I have to say that— when I was riding— I threw many spears (and hit the target) against bears, boars and deer; but I have also failed many times due to several factors such as the beast's movements, my position on the saddle, the wind, the uneven ground, the wrong choice of the point to handle the spear, its weight, or being too hasty and not having prepared the throw as I should have; therefore, do not consider it odd whenever your spear misses the beast because there are many factors that can cause just that.

And, as far as this art of throwing the spear is concerned do not forget that it is worth to practice it and to acquire the skills needed to master it even if —for obvious reasons — it is of no importance to those who wear a braçal.

It is an art very useful in many situations namely hunting, playing with canes and doing other things that are usually done by good men, either mounted or on foot.»

Chapter XIV of section 5:

«As far as advice for a rider to wound effectively using a sword are concerned, there are in my opinion four main ways to do it:

First, to wound with the cutting-edge of the sword, performing a horizontal rotation with the arm that holds it.

Second, to wound with thecutting-edge of the sword, performing an oblique rotation with the arm that holds it.

Third, to wound with the cutting-edge of the sword, performing a vertical top-down movement with the arm that holds it.

Fourth, to wound with a thrust of the tip of the sword.

The first two are — in my opinion — the best ways to wound another rider; and to cause great wounds with a horizontal rotation of the arm that holds the sword, you should use the combined forces of the horse's gallop, of your upper body and of your arm, all together. This was the solution I have found more efficient in tournaments; if the horse was not at gallop and 1 used only the force of my arm, the stroke was much weaker than if 1 could use the three forces simultaneously.

This is now an advice for all those who want to make perfect, harmonious and beautiful strokes with a sword: when you are coming back against your adversaries (assuming you have passed through them the first time without being forced into or attempting any collision or engagement), you firm your legs on the saddle, you keep your upper body and the arm holding the sword loose and relaxed with the sword strongly held in your hand and you do your stroke not rotated, not top-down, but with obliqueness of the arm that holds the sword deeply strongly. And to have time to prepare yourself, you should not make (in important tournaments, with many riders) short turns with your horse and you should also not choose in advance any specific adversary, unless you are sure to be in great advantage over him (like for example, if he has his back to you). (...)

And if you need to wound fast with a stroke of your sword (and time might be a decisive factor in the situation you are facing) you should just use an oblique rotation of the arm that holds the sword, not spending any time to prepare for the simultaneous rotation of your upper body in order to ensure a more decisive wound. [emphasis of my own on this particular important feature of the jogo, oblique slanted attack]

The third stroke (a top-down movement of the arm holding the sword) is rarely used against other riders but it is advisable against adversaries on foot or against alymarias [archaic Portuguese term for animal beasts]; you should hold the sword strongly in your hand and transfer all the strength of your body to the stroke in order to cause a great wound; in this technique— the transfer of the strength of your body to the stroke in the top-down movement of your arm holding the sword — it is very important to avoid wounding your foot or your horse with the sword.

And remembering what I said about the importance of the habit of learning all arts, those who want to learn this art must practice it frequently, which is the only way not to forget it; if you master it, you will find yourself at an advantage in many specific situations.

One final advice to those who want to keep their arms in good physical condition (which is also important for the throwing of the spear): you should not play peella [a medieval/early modern ball game] or throwing things too light or too heavy as it might only cause damage to your arm and it doesn't bring any benefit.

The fourth option is to wound with a thrust of the sword's tip.

The technique is similar to the one described to wound with the spear de sobre-mãao [archaic Portuguese for sobre-mão/over-hand]:

Holding the weapon in your hand (horizontally) and pushing forward with your body. You can wound an alymaria keeping your sword pointing to the outside (relatively to your horse) to avoid having the alymaria — after it is wounded — attack your horse's head; the safest way is to cause a deep wound in the alymaria with the sword (using your body's weight to push forward your sword's tip into the alymarias body).»

And chapter I of section 6:

«Throwing canes or any other things

Much as in the first example, there are those who wound the beasts too much with the spurs at the start of their gallop and have so much attention on the throwing itself that they stop using the spurs and the beast stops; the solution is like the one referred in the first example: the beast should not be wounded with the spurs during the run but only a few moments before the throwing; the spurs should be used with energy' and the throwing should be done simultaneously with the beast's increase of its pace.»

By the late-16th century, Jeronimo Carranza had promoted across the west the "true dexterity" of fencing with only one hand, making less popular in the west the before dominant worldwide (see Japanese kendo) two handed fencing (like in jogo do pau), but two Portuguese, fencing instructor Domingo Luis Godinho and artillary general and fencing instructor Don Diogo Gomes de Figueiredo, decided to promote the old way of Montante fencing in Arte de Esgrima ("Art of Fencing", 1599) and Memorial Da Prattica do Montante Que inclue dezaseis regras simples, e dezaseis compostas Dado em Alcantara Ao Serenissimo Principe Dom Theodozio q[ue]. D[eu]s. G[uarde]. de Pello Mestre de Campo Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo, seu Mestre Na ciencia das Armas Em 10 de Mayo de 1651 ("Memorial of The Practice of Montante Which includes sixtee simple rules, and sixteen composed ones Given in Alcantara to The Most Serene Prince Don Theodozio m[ay]. G[o]d. K[eep him]. out of By Aide de Camp Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo, his Master in the science of Weapons On 10 of May of 1651") respectively. And right on time that the latter did so, since northeastern peasants to whom weapons had been taken-away to form the new Portuguese army after the restoration of independence in 1640, needed easier two handed techniques for the fencing with wooden tools they often were forced to resourt to when only self-defense with guerrillas could protect them from Spanish incursions. Both of these methods had the focus in a common jogo do pau scenario of someone being assaulted suddenly by several assailants.

In traditional oral (hence hard to date in origin) Portuguese culture, many spots of northern Portugal had stick fighting included in celebrations of local pilgrimages, and boys were normally given their own staff at the first growing of beard. During monarchist years, everyone from the king to the simple peasant could be seen practicing it. Before and after the 1910 republican establishment, a staff was considered as much the part of the garbing of the common citizen as a cap or a scarf on the neck (although by the 1910s the staff was fading as tool of fight over a girl's affections to canes). The game was also taken to colonial Brazil (in the 18th century, Manoel Rodriguez or Mandú-Assú/"Big Manuel" was renowed for fighting Mato Grosso do Sul natives with a beanbagpole when out of musket bullets and in 1850 a Portuguese sailor similarly fought Rio Grande do Sul natives), where it fused with African-origin stick fighting brought with blck slaves, and became particularly common in northern Brazil. Two poems from the 1790s, Francisco de Paula de Figueiredo's Santarenaida: poema eroi-comico ("Saintarenaide: mock-hero poem", 1792, describing a game of stick fencing practiced in a pilgrimage) and B. A. de S. Belmiro's “Versos de B. A. de S. Belmiro, Pastor do Douro” ("Verses by B. A. de S. Belmiro, Durius Shepherd", 1798, in which in a neoclassical buccholic setting, shepherds quarterstaff fight for a shepherdess) are the first mentions of jogo do pau by name(s) and precise stylings in writing in Portugal.

A possible 18th century episode, which was already known by the early 19th century (as shown by an idiomatic mention of the expression "Fafe Justice" by Jose Valerio Veloso's French invasion chronicle Memoria dos factos populares na Provincia do Minho em 1809, Reimpressa, e augmentada de novos acontecimentos ("Memoir of the popular facts in the Minho Province in 1809, Reprinted and augmented by new happenings", 1823) and got retold in a 1960 long poem by Inocencio Carneiro de Sá under the "Barão de Espalha Brasas" (something like "Baron from Hair Trigger") pen name in the collection Lira Maluca (this is one of the possible legends explaining the expression "Fafe Justice"), tells of the Viscount of Moreira de Rei at the time being insulted during Fafe municipality politics by a Marquis, deciding with the former to sort it out in a duel by stick, a form of fight that the Viscount dominated, avenging his honor.

The stick was the main weapon of peasant uprisings against the French napoleonic Invasions of Portugal of 1807 and 1809-10 (as confirmed by a report of peasants with farming utensiles and sticks beating out Frenchmen on the issue 9 from July 21st, 1808 of the newspaper Minerva Lusitana, and probably more aided by a peasant attempt to follow the military martial arts style of spear fighting proposed in 1809's anonymous Methodo de manejar o pique ou lança/"Method of handling the pike or lance", also describing spear-handling as "game" in the sense of martial arts/arm handling, and refering the jogo of the Atirador do pau/Stick thrower by name but deeming it inferior to pike/lance jogo despite some similar fighting stances due to the lack of lethal tip making the Atiradores more exposed; all this earned a guerrilla with (vara)pau a place in the Lisbon Monument to the People and to the Heroes of the 1808–1814 Peninsular War), during the Liberal-Absolutist civil wars of 1828 to 1834 and the 1846 Maria da Fonte popular revolution (in which, as in all previous folk guerrillas, sickles tied to long sticks were sometimes handled in the way of the jogo as both Father Casimiro José Vieira and Camilo Castelo Branco put it in their books on the Minho revolution, an idea proposed for the Portuguese army by officer António Joaquim de Barros Lima, in service since 1828).

At first restricted to northern Portugal, migrations from the north to the Ribatejo region in the 18th-19th century had it spread its usual scope of practice expanded forever, including the taking by colonial settlers and banned outcasts (as José da Costa, who lived at late-19th-century Catumbela, Angola, or Joao Ferreira in the Negage, also Angola, but the 20th century one) para as colónias (trully becoming a pan-Portuguese sport). Maybe the first known master of the jogo was the bulky early-mid-19th century's José Braz Arroteia from Ortigosa (Western Region), who even gave the absolutist king Don Michael/Miguel lessons. Similarly to the presence of the quarterstaff fights in Robin Hood media, the 19th century "Portuguese Robin Hood" figure, "social bandit" José Teixeira da Silva from the place of Telhado («Rooftop») or «Zé do Telhado/Cheo [as short for Jose] from the Rooftop» (who seemed to be a practicioner of it in real life) has jogo do pau present in his own media from the 19th century onwards. By this century it did appear its first proper manual, 1885's Oporto-published Arte do jogo de pau ("Art of the game of stick") by Joaquim Antonio Ferreira.

Probably the oldest drawing of jogo do pau combat and not just of the clubs out of combat (as in one engraving for the first edition of Rodrigo Paganino's 1861 Os Contos do Tio Joaquim/"Uncle Joaquim's Tales" or one engraving for Alberto Pimentel's 1904 historical novel O Lobo da Madragôa/"The Madragoa Neighbourhod Wolf") is a drawing by artist, writer and composer (having composed the future Portuguese Republic's national anthem) Alfredo Keil for his own 1907 short story book Tojos e Rosmaninhos: Contos da Serra ("Furzes and Rosemaries: Tales from the Ridge").

The 19th and 20th century has no lack of episodes in which some sort of brawl with (vara)paus happened with much violence, maybe the most famous being the 1910s (vara)paus brawl when people from the village of Soajo went to the town of Arco de Valdevez to avenge a townsfolk of theirs mistreated there. But in 1895 the sport gained respectability outside the lower classes, with the beginning of practice and classes at the Lisbon Gymnasium Club under Pedro Augusto da Silva, Domingos Salreu and Artur dos Santos, "officialising" the Lisbon school of jogo do pau which was starting to be lovingly nicknamed a esgrima nacional ("the national fencing") as taught in the last few decades before by its modern (re)founders Joaquim Bau and Joaquim Maria da Silveira (both teachers to dos Santos, da Silveira having been master to Salreu and da Silva), besides performances at royal family soirees. In the early 20th century, Joao Quinteiro founds the Jogo do Pau Centre of the North, and the already mentioned Joaquim Bau was a wandering teacher who taught for sustenance donations from his native Coastal Douro and Oporto's Marco de Canaveses to the central-southern Ribatejo, the western central-southern capital Lisbon or even the northwestern hinterlander terras de Basto).

The oldest (surviving) filmed fotage of jogo do pau is fotage of a practice for bayonete use with staffs among soldiers of the WWI Portuguese Expeditionary Corp at Roffley Camp, Inglaterra, on August 15, 1918. Since the beginning of the sound era,on fictional Portuguese film, simultaneously with some promotion of the "match"/"fare" as sporting healthy activity by the Portuguese New State dictatorship in public demonstrations and practicing activities within the paramilitary Legião Portuguesa ("Portuguese Legion") and boy/girlscout-like Mocidade Portuguesa ("Portuguese Youth"), staff fighting as rehearsed practice and brawl technique within the plot is shown in (then) current setting films like "Gado Bravo ("Wild Cattle", 1934) or Aldeia da Roupa Branca ("The Village of White Clothes", 1938) or in period films like A Morgadinha dos Canaviais ("The She-Majorates of the Reeds", 1948, in whose jogo do pau scenes the Lisbon esgrima nacional school members master Pedro Ferreira and Antonio Sacadura are extras) or Camões ("Camoens", 1946).

By the 1980s, new teachers created methods of teaching it and practicing similar to Japanese kendo (including padded protected costumes), like the Escola de Esgrima Lusitana do Santo Condestável ("Lusitanian Fencing School of the Saint Constable") method taught by Mestre Nuno Russo. The staffs are conventionally between 1.5 meters and 2 meter (4.92 feet and 6,56 feet) in length, and made from chestnut-wood, quince-wood, lote-wood or ash-wood. The basic technique difference from, say, Robin Hood style quarterstaff fighting is that instead of the staff being held with two hands near its two ends and being used to hit with both ends, in the Portuguese equivalent the stick is held near the end closer to the holder with both hands and handled as if a sword. Besides that and the techniques already above described, the essential is that in sporting combat the objective is to cast the blow pointing to the opponent's stick and not to the body or hands of the former. Among other attacks like blocks there re blows like the so called talhos ("carvings", by the rightside) types of "jogos" ("castings")/"ataques" ("attacks") or the so called reveses ("reversals", by the left, also called enviesados/ "obliquely" or arrepiados/"deadset-against" attacks).

Main sources:

Antonio Franco Preto, The Royal Book of Jousting, Horsemanship, & Knightly Combat, The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005

Na literatura ("In literature"), Jogo do Pau Português ("Portuguese Jogo do Pau") website

Provavelmente a mais afamada arte marcial portuguesa é o jogo do pau (também conhecido em Portugal como jogar as canas, ou combate a/jogo de varapau), uma forma de esgrima com pau partilhada por Portugal e a região espanhola vizinha a norte e aparentada da Galícia/Galiza (especialmente nas áreas em torno do rio Minho/Miño fronteiriço e galego, ao ponto que o Galego Xanquin Lorenzo Fernandez propôs uma origem portuguesa à sua presença na raia galega). Não é sabido com exactidão quando ou como ele começou, nem quão antigo é. Como muitas artes de luta com pau similares, veio principalmente de camponeses practicando e combatendo (principalmente a salteadores/invasores ou para acertar pequenas querelas) com ferramentas agrícolas ou clavas facilmente feitas e lança (larga) a partir de ramos de árvores que podiam encontrar em todo seu entorno na campo e bosques, e fidalgos do campo practicando lutas com espada com armas menos letais e danos, similar a samurais practicando com espadas de madeira do kendo ou os Tameis combatendo por desporto ou intenção danosa com bastões jogando silambam. Essas causas na raíz da sua sua origem estabelecidas, a sua origem poderia ser tardo-medieval (o Rei Fernando criou a 12 de Setembro de 1383 a primeira corporação policial, os Quadrilheiros com varas de 8 palmos/1,76 metros e uma vara verde com o escudo e quinas das armas reais portuguesas, e como mostrado numa iluminura da Recueil des Croniques et Anchiennes Istories de la Grant Bretaigne, à présent nommé Engleterre/"Recolha das Crónicas e Antigas Histórias da Grã-Bretanha, ao presente nomeada Inglaterra" de Jean Wavrin foi a arma comum do exército português na batalha de Aljubarrota na Região Oeste), mais no iniciar da Idade Média (parece que durante a reconquista cristã, bastões eram carregados e usados como armas por pessoas a pé como o lendário Frei Hermígio "Basto Eu" Romarigues de Terras de Basto, e até a cavalo, e ordálios, julgamentos por combate, eram combatidos por camponeses com varapaus até a Igreja Católica começar a supri-los pelo século XIII), romana ou até pré-romana. Só há referências claras a ele pelo século XVIII. Mas algumas raízes iniciais do seu estilo e técnicas de luta podem ser encontrados numa fonte inesperada e real.

O Rei Dom Duarte (nomeado no seguimento do seu bisavô Eduardo III de Inglaterra, visto que Duardos ou Duarte são versões arcaica/aportuguesada de Eduardo), «o Eloquente» ou «o Rei-Filósofo», é mais conhecido (devido a um mero reinado de 5 anos, até morrer de peste, começado quando já tinha 42 anos de idade) como um legislador cerebral e homem de letras o qual permitiu ao seu irmão o governador da Ordem de Cristo Infante Dom Henrique, «O Navegador» organizar e financiar navegações (não conquistas) das costas sul-marroquinas e do Sáara, e cujos exércitos falharam conquistar Tânger e depois das Cortes de Leiria de Janeiro de 1438 onde só ouviu e não falou até finalmene decidir não render a praça de Ceuta em troca do seu irmão capturado em Tânger Fernando, e os seus livros O Leal Conselheiro como um guia de governar moralmene com as primeiras páginas sobre o tópico da saudade portuguesa e Ensinança de Bem Cavalgar (traduzido (com algumas liberdades) para Inglês como The Royal Book of Jousting, Horsemanship, & Knightly Combat) a princípio parece só seguir nas pisadas do Livro da Montaria do seu pai João como guia sobre uma actividade nobre popular, dando desde então a imagem de um rei, livresco, desligado e "mole", numa palavra "não-físico"; mas de perto e em pessoal, Duarte era (como o cronista dele Rui de Pina aponta) um homem práctico e próximo da natureza do Renascimento e Descobrimentos, entusiasta practicante de caça, esgrima, justa e luyta (Português moderno luta). Assim Duarte é mais correctamene uma figura à Miyamoto Musashi, um guerreiro cavaleiresco do bem-pensante o qual também escrevinhou regras do seu tipo de combate e sua filosofia subjacente.

A Ensinança de Bem Cavalgar não é só o possível primeiro manual de equitação europeu, mas um manual sobre toda a sorte de actividades que podem ser feitas a cavalo, incluíndo lutara cavalo (e practicá-lo a pé) usando espadas ou paus (e usando paus para acalmar cavalos enquanto são cavalgados). Devido a isto, as dicas de luta dele (as quais são detalhadas o suficiente que o foco a-cavalo de frases anteriores é quase esquecido em muitas frases subsequentes) com essas armas têm sido consideradas pelo duo promotor/practicante de jogo do pau de Antonio Franco Preto e Luis Preto como descrições primevas de jogo do pau (o que é provavelmente o porquê do combate a pau português sair tão similar às artes marciais europeias de esgrima de espadachim de técnica de-duas-mãos Montante e combate blindado Medieval Béhourd), e Duarte (visto que era o livro dele para pôr o que quisesse nele) até dedicou algumas páginas à luyta (cujas técnicas descritas são bastante cerca de outra art marcial portuguese que cobriremos mais tarde, a galhofa de Trás-os-Montes e Beiras).

Tudo isto ficando assente, a apresentação pelo erudito e escritor Cândido de Figueiredo de um homem com um cajado defendendo-se de dois agressores de naifada na 1.ª viagem de Vasco da Gama com técnicas de jogo do pau pode ser historicamente fidedigno mesmo se não plenamente documentalmente confirmado. Assim ele detalha técnicas de lança/cacete/varal no capítulo II da I parte do livro, capítulo V II parte, capítulo II da IV pare, capítulo V, capítulo VI, capítulo 7, capítulo X e capítulo XIII da V parte, e capítulo I da VI parte, e técnicas de espada no capítulo VIII, XIX e XXI da secção 1, capítulo II, III e XIV da secção 5. Iremos passando através de todas as passagens que tais.

Capítulo II da I parte:

«No tempo da paz recebem os que desta manha husam grandes uãtageẽs em justar, tornear, em jugar as canas, reger alguã lança, e sabella bem lançar. E assy em todas outras manhas que acauallo se fazem que som muyto husadas em casa dos senhores Por q̃ em todo, segundo oq̃ naturalmente hã percalçado de cadahuã dellas, assy recebem per seerem boos caualgadores uãtagẽes sobre os q̃ tais nom som, ajnda q̃ per saber delles e perposiçõ dos corpos jguallados seiã. E pera seerem boos monteiros lhe faz conhecimẽto grande auãtagẽ em poderẽ melhor sofrer os grandes encontros, e seerem soltos, e auysados pera bẽ ferir, e fortes em suas sellas, e sabedores em sofrerẽ bem seus cauallos, e saberẽsse delles ajudar onde e como compre, e se guardarẽ de muytos perigoos. Todo esto, e outras cousas q̃ na terceira parte serom declaradas, sõ muyto nescessarias saberẽ os q̃ boos mõteiros desejõ seer.

Darlhes mais auantagem debem parecer, e os senhores terem delles per ueerem q̃ som boos caualgadores algũa parte deboa presunçõ pera feitos deguerra, e doutras boas manhas q̃ muyto ual. Eos prezã per seerem seguydos, os outros em teerem boos cauallos, e os saberem bẽ caualgar, e correger, e auer em sua casa muytos e boos caualgadores, e bem em caualgados da q̃ amayor parte dos senhores muyto praz. E ajnda lhe pode prestar per se demonstrarẽ onde quer q̃ som scudeiros, e podem logo fazer tal manha, per q̃ sejã preçados, e conhecidos, q̃ som homeẽs pera feito e criados em boa cõta seos outros geitos razoadamẽte ẽ elles uyrẽ.»

Capitulo VIII da I parte:

«Da besta não podemos ser derribados senão pera hũa das quatro partes: pera deante, e pera detras, ou pera cada hũa das ilhargas. Pera deante me pode derribar anteparando ou pullando tornar a poer as mãos acerca onde as tinha, como algũas bestas fazem, com malicia, ou lançando as pernas, e mettendo a cabeça antre as mãos em acabando de pullar, de correr, de outra desordenada guisaou em saltando alguũ feito, tendo abesta geito de saltar sobre as maãos, e lançandosse de sospeita por hũa barroca abaixo, vallado, por outro semelhante lugar, ou embicando, posto que a besta se tenha, e parando quando corre, sobre as maãos. Pera tras me pode derribar alvorando, pulando, saltando logo no começo, começando a correr, subindo ryjo por huũ lugar muyto agro de sospeita, ou muyto spesso que alguũ matto me torve e caya por desacordo. Pera hũa parte ou aa outra posso cayr spantandosse ao traves, voltandosse ryjo, furtando a espalda quando pulla, lança os couses, ou começando danteparar desvyandosse a cada hũa das partes. Posso ainda ser derribado pera cada hũa destas quatro partes per força que me seja feita, ou regendo algũa lança, lançandoa, cortando om espada, e fazendo algũa outra cousa em a qual nom me sabendo bem teer posso cayr, ainda que a besta nom faça porque me deva derrubar.»

Capítulo XIX da I parte:

«E ja daquesta quisa vy cayr alguũs querendo reger algũa lança : tanto se apegavam com ela que a nom podiam teer, ou levantar quando ella caya no chaão, elles lhe tinham companhya. E assy em lançando, tanto teem alguũs teençom em muyto lançar, que, desemparandosse da besta,, com a lança se vaão fora da sella! E assy acontece em cortando com a espada, ou ferindo de sobre-maão, ou fazendo outra qualquer outra cousa, quer desamparandosse da besta, em teer cuydado ao que ham de fazer, caaem muytos com desacordo e myngua de saber.»

Capítulo XXI da I parte:

«E ja daquesta guisa vy cayr alguũs querendo reger algũa lança, tanto se apegavam com ella que a nom podiam ter, ou levantar quando ella caya no chaão, elles lhe tinham companhya. E assy em lançando, tanto teem alguũs teençom em muyto lançar, que deseamparandosse da besta, com lança, se vaão fora da sella. E assy acontece em cortando com a espada, ou ferindo de sobre-maão, ou fazendo ura qualquer cousa, que desamparando-se da besta.

Em teer cuydado ao que ham de fazer, caeem muytos com desacordo e myngua.»

Capítulo V da II parte:

«Mes deve usar todallas sellas, e monte, e caça, e reger, e lançar; e no reger, com leve lança de que seja bem senhor, seja ensynado a levar e trazer boo geito e contenença; e no lançar esso medes, com cousa leve razoavelmente se filha mylhor o geito da braçaria. E devemos guardar todollos, que dello pouco souberem, de lançarem cousa que seja aguda dalgũas partes, porque da hũa por entrar n chaão, e da outra por a ponta ficar contra quem a lança, se pode della receber grande cajam; e porem cana, ou paao rombo damballas partes, e de peso razoado, segundo a grandeza do moço, he boa pera esta manha mais sem perigo saprender.»

Capítulo II da IV Parte:

«E por reger algũa lança, ou a lançar, u fazer algũa outra cousa, el seja assy firme do corpo, que sem embargo que lhe a besta faça, el possa soltar seus pees pera a ferir, e as maãos pera a lança e rédea, pera toda outra cousa, andando armado, ou nom trazendo armas, e tam sem empacho como se de pee o fazia, ou se a besta fosse passeiando.»

Capítulo II da V parte:

«E bem tenho que mais leixam de percalçar as manhas per myngua da voontade e fraqueza della, que por desposiçom do corpo, ainda que sem duvyda alguũs naturalmente som tam stremados cavalgadoresque poucos acharom seus semelhantes, e outros assy empachados que a gram trabalho lhe faram aver boa soltura; mais leixando estas cousas que som naturaaes, e falando do que ao ensino perteence, em estas quatro partes convem de se aver a soltura:

A primeira, a do braço dereito para reger, lançar, cortar, e fazer qualquer cousa.

A segunda, da maãos, e do braço esquerdo, pera trazer a redea, e a soltar, e teer, e soltar a cada hũa das partes como viir que compre.

A terceira, as pernas do giolho a fundo, pera ferir a besta quando e como cumprir.

A quarta, he da contenença do rostro e do corpo, segundo ja screvy onde falley da segurança.»

Capítulo III da V parte:

«E as principaaes som, segundo meu juyso, ensayarse armado de guerra, assy corregido como em ella deve andar, justar, tornear, avendo boo meestre ou meestres, que avysem no que comprir,

E elle creya o que lhe disserem, e lhe obedeeça, porque necessario he ao que aprende creer, e obedecer saquel que o ensina.

E esso medes da grande ajuda aa soltura o andar do monte e caça, e reger lanças, e remeçallas, jugallas canas, ferir despada. E todas estas manhas devem ser husadas per aquelles que boa soltura a cavallo desejam daver, porque boa e razoada husança he grande meestre, e sem ella nom se pode nenhũa percalçar, e ainda que aja, se torna bem ligeiramente em esquecymento.

E continuando na teençom que o primeiro screvy em mais algũas querer aproveitar, (que me guardar em esto que screvo poder seer contradito dalgũas) que a cavalo muyto som husadas pera os que pouco dellas sabem quero dar algũas ensynanças. E'som estas: do trazer a lança (so maão, na perna, ao collo); regella, e encontrar com ella, feryr sobre-maão; remessalla bem e certo; e despada ferir de ponta e de talho. Porque em esto se mostra grande parte da soltura. E sobrello escreverey brevemente, segundo per mym achey certa pratica ainda que nom de razom de todo, ca se outrem provar o que se screvo, e bem acertar a manha a esperiencia lhe mostrara se fallo certo. E nom devem estas manhas seer desprezadas de nenhuũ cavalheiro ou scudeiro, pensando que nom som necessarias, mes antes se devem todos trabalhar por sabeerem dellas. (...)

E devem teer teençom que assy como nom som embargados de trazerem contynuamente suas espadas cyntas, e muytos hi ha que muy pouco ou nada dellas se aproveitam, mes solamente por entenderem que em alguũ tempo de mester lhe podem prestar lhes praz de as trazerem, que assy do saber das boas manhas o coraçom daquel que as bem ha razoadamente recebe prazer e contentamento, conhecendo que se lhe comprir pode dellas receber boa e grande vantagem sobre os outros que as bem nom sabem; e que muytos foram e som dellas em grandes necessidades accorridos e ajudados, e pera boos pera boos feitos theudos em mylhor conta.»

Capítulo V da V parte:

«Quando alguũ ensynarem a reger de pee, estando quedo lhe devem mostrar todollos avisamentos , que sobrello avera de teer, com algũa leve lança, ou paao, com que folgadamente possa. E som estes:

Primeiro, do filhar da lança quando, a teem na perna, donde todos mais custumamos reger.

Que a maão meta de so ella, e quando poseer no peito quee chegue a maão de so o braço o mais que poder; e quando poseer no peito quee chegue a maão de so o braço o mais que poder, e dobrea de tal guysa, e assy que o peso da lança lhe venha todo sobre a chave da maão, e nom sobre os dedos.

E des que alguũ de pee assy for ensynado com leve lança, devesse de ensynar com outra mayor, e tanto yr crecendo ataa que chegue ao mais que bom poder reger, porque tal cousa com que bem nom possa nom deve custumar por nom quebrar, e door dos lombos, da cabeça e das pernas, e da maão que dello sem proveito recrece. E des que de pee sentir que bem sabe reger, deve a cavallo paseiando provar assy como de pee aprendeo, e tenha quem o avise do que vyr que mal fezer; porque a contenença que leva per sy, sem grande saber da manha e husança nom pode conhecer, se per outrem nom for avisado; e des que o bem fezer deve gallopar, e des y correr.(...)

E quando a ouver de metter de so o braço levantea que o conto vaa bem arredado de so el, e como ally for carreo , e aperteo quanto mais poder, fazendo alguũ peito, nom por se torcer nem derrear, mais estando dereito por filhar em si o folego. E dalgũa pequena contenença do corpo o saiba fazer. E o levantar deve seer de sollacada, dandoa do corpo e do braço, e da maão, porque hũa grande lança se levanta melhor desta guysa que doutra, e tanto que lhe deer a sollacada ao cayr do collo, deve arredar o braço, e desvyallo aquella maneira que ja disse que a lança ao colo se devya trazer. Dobrea de tal guysa que faça della restre [placa de metal dando apoio à lança], e assy que o peso da lança lhe venha todo sobre a chave da maão, e nom sobre os dedos. E a lança nom descaya mais baixo que a sua cabeça, mais em aquella medida a leve ataa que a levante como suso he scrito, e a lança nom leiche descayr ryjo, mais huũ pouco alto a arrecade no peito do braço e da maão, e passo a leixe viir aaquella altura em que a entende levar.

E aquesto presta muyto ao reger sem restre, porque a lança he ajudada de tres partes, scilicet, hũa da maão que sustem, outra do apertar do braço que a soporta, e a terceira do peito sobreque grande parte he encostada. E se rouver a rondella [peça de guarda firmemente fixada à racha da lança para protegera mão do cavaleiro], guardesse que nom lhe fique tras o collo, por quanto he muyto feo, e se pode com ella ferir se andar desarmado.

(...)

Se a lança tever gozete [apego à lança pra ajudar o manejador a segurar e manejá-la], ou rodagem de coyro, a maão chegue ella quanto mais poder, poendo alguũs dos dedos sobrel, e aqueste geito, regendo com restre ou sem ella; sabendo bem sem restre, mais ligeiramente o fara com ella.

E regendo tenha tal maneira com esta suso scripta no levar da perna, e a metter so o braço [Português arcaico para sobre o braço] e alevantalla mais deve aver huũ avysamento que o braço levante; e de com o conto da lança em el contra o o cotovello de nom topar de so a restre. E como ally chegar, çarrando comsygo a faca em casar na restre, e a lança soporte alta em tal guisa, que a nom leixe cayr ryjo, mais assusseguea huũ pouco mais alta, e entom a leve naquella altura que a quiser levar.

(...)

Des que a lança vay de soo-braço [Português arcaico para sobre-braço] se podem fazer estes erros, scilicet, derrearse com ella, encostarse a maão dereita.

(...)

E dobro aqui algũas razoões por dar aazo de se melhor entenderem, porque mais reguardo no que sobreposto screvo de seer claro que fremoso.

Se do pesco[ço] regeer e for sem restre em a derribando carre com sygo o braço, e todavya se guarde de leixar descayr como suso he dicto.

E se levar restre assy de com o conto da lança no braço contra o cotovello, e dally a çarrando a encase na restre; e sempre se avyse do descayr por a soportar na maão, e leixar assentar folgadamente.

Ha hi outra maneira de tirar lança, e a lançar no braço esquerdo, e dalguũs he louvada per melhor que outra pera pelleja, porque dizem que dally a tornam cada vez que lhe praz mais ligeiramente, e essomedes que podem bem feryr aaquella ylharga e pera tras.

E quando se levanta ao ombro, se a lança tal he, alguũs a leixom cayr sobraquello braço dereito pera defender contra tras; e outras vezes leixom descayr a ponta da lança ao chaão, e dally a tornam o ombro e a regem.

E todas estas maneiras de reger som muyto boas daprender e husar, por quanto podem prestar em tempo de mester; e em as husando os homeẽs se fazem mais soltos cavalgadores.

Mes de reger duas outras lanças, nem dar voltas com ellas per cima da cabeça, nom me embargo descrever por nom seer cousa de prestar.

Ainda que os homeẽs em bem fazendo mostram boa soltura.

De que a lança vai de soo-braço sem podem fazer estes erros:

• Scilicet derrearse com ella encostarse aa maão dereita, ou muyto sqyunado

• yr mal assessegado (...) dos pees, pernas e cabeça, corpo e vara

• e levalla [a vara] muy atravessada

• ou (...) para fora, ou muyto alta ou baixa

• ou derribada a cabeça (...) sobre a lança, ou muyto alta pera detras

E quem a bem quiser levar guardasse de todos estes erros, e levalla como a mym parece que he melhor.

(...) Em justa custumam em nesta terra lançar vara aa maão esquerda, e aa maão dereita. E se for aa mão esquerda devesse dar ajuda e balanço do banzear do corpo pera aquela parte, levantando bem o braço dereito e leixalla yr contra tras; se a parte dereita a quiser lançar, o melhor e mais seguro pera sy e os que estam na tea [ver mais abaixo] he, como a levantar, lançar a ponta pera tras e o conto pera diante. E desque ambos estes geitos se trazem em custume, a maão, corpo e braço filham dello tal mestria que sem trabalho o fazem, como huũ bom tangedor que os dedos lhe vaão aas cordas, ou o caçador que com a maão esquerda sbe guardar todo o jeito que a ave requere, o que a dereita nom pode fazer, ainda que per entender assyy sabe pera uma maão como pera outra.

E per estes exemplos se pode conhecer como e quanto he necessario cada huũ aver tanta usança da manha que o corpo e as partes de que em ello se deve servir tenham tal habito e saber como della requere.

Huũ avysamento per mym achey

Huũ avysamento per mym achey quando desarmado regia algũa grande e pesada lança, que ao que ao alevantar della, ante que sobre ho ombro me caysse, eu a leixava correr per a maão huũ pedaço:

• e aquesto fazia por fycar mais quedo na sella, e por o grande seu peso me nom dessassegar, e penso que se per alguũs for custumado em tal caso que acharam grande avantagem, se o bem souberem fazer;

• E podem alguũs em reger ser torvados, ainda que bem o saibam, por serem mal armados, e os torvar o restre, braçal [armadura protectora do braço] algũa outra armadura corregimento seu de de seu cavallo, ou por seerem atrouxados aalém do que folgadamente sem trabalho podem bem andar; e porem he necessario ante que o de verdade ajam de fazer que primeiro se ensaem, ou que sem outro correr de cavallo ponham sa lança no restre tres ou quatro vezes, e assy saibam todo correger que nom levem cousa que os torve. E posto que sejam ensayados alguũs dias, conveem que ante provem tres ou quatro vezes de poer a lança na restre assy armados de todo com elles entenderem pellejar, correr pontas ou justar aquella ora que o fazerem ouverem, porque he necessaryo pera o reger e saber em como veem pera encontrar (segundo adiante sera dicto).

E se alguũ quiser reger sobre roupa, deve resguardar se he de tal guisa que torvar o possa, e aquesto se for de seda ou chapada, porque nom se rege bem sobrella, ou se a manga do balandraao assy feita que nom leixe bem meter a lança de so o braço.»

Capítulo VI da V parte:

«Por dar ensynança pera bem encontrar em justa monte, escrevo avysamentos, que me boos e razoados parecem; e delles se pode filhar enxempro pera todo tempo que desta manha se posta prestar.

Prymeiro na justa, que he mais principal, os homeẽs leixam de bem encontrar por:

myngua da vista, de governar as lanças, (...) de segurança de suas voontades.

[neste capítulo, neste capítulo, (...), no quarto capítulo a seguir(...)]

E quanto aa vysta

E quanto aa vysta fallecem alguũs por (...) os olhos em se apertando aa ora do encontrar, e nom se conhecem pollo fazer muyto trigosamente! E outros ainda, que o entendam, assy som forçados de sua condiçom que lhe nom consentem em aquel ponto que o encontro topa de os terem abertos. Outros, de se mal saberem armar do elmo ou do escudo perdem da vista.

E alguũs, por nom saberem tornar corpo pera encontrar e gaanhar a vista, volvem os olhos somente no elmo e cabeça, por levarem sua contenença dereita leixam de veer ao tempo dos encontros. E pera remedio destes quatro erros he grande avantagem trazer com sigo tal pessoa, que no cabo da carreira pergunte o que justa per hu errou ou tocou, ca se ryjo encontrar nom se pode certo saber, e se vyr que nom concerta todallas vezes logo que lhe diga que nom vee, e quanto desvaira da verdade, e que se avse de nom çarrar os olhos; e desta maneira pode scusar o primeiro suso dicto.

E quando a condiçom he tal que contra voontade forçadamente çarra os olhos, he muyto maa de correger; porem sendolhe ryjamente desdicto per aquel que com elle anda, lhe fara de sy aver desprazer e manencoria, e com ela mais ligeiramente se pode forçar, e esso medes he bem de lhe dizer per onde erra, ainda que el nom possa conhecer.

E tanto que errar duas ou tres vezes, por buscar tarde, digamlhe que se avyse de buscar cedo, por tal que nom encontrando per boa vista encontre per esmo, e se desventuira ouver daver algũa boa esqueença, o acrecentamento do prazer e da voontade lhe dara esforço de ter os olhos abertos aos encontros.

E o maao corregimento no ensayar e no armar se pode bem correger, assy:

quando pera a justa de todo for armado stando a cavallo, el meta a vara de so braço, e assy tenha seu elmo e escudo corregido, que ainda que se mova de hũa parte pera a outra, e tendo a vara em aquella altura que deve encontrar, sempre de veja ameetade della, ou o menos o terço, e dally avante ataa o cabo da carreirae se nom poder assy fazer logo se correga, ca segundo nosso custume nom entendo que possa bem encontrar quem assy nom vyr.

E pera bem filhar a vista do elmo eu achey boa maneira atallo de tras primeiro naquella guisa que bem poder filhar, e desy apertallo de diante, e assy o elmo fica mays firme, e certo na vista, que se o primeiro diante liarem que detras.

Pera bem ver ao tempo do encontrar ha mester que assy como ho outro vem pella tea [tea em Português arcaico e tei em Português moderno, a barreira separadora do campo de justa dos espectadores e a separadora de ambos os justadores], que assy venh todo o corpo aderençado a elle, e quando veher ao encontrar o rostro volte contra el quanto poder assy que o veja de dereito , e nom pello quando da vista do elmo. E aqueste geito presta muyto a ganhar boa vista, e encontrarmelhor, e sofrer os encontros.

E quanto a segunda parte pryncipal de governar a lança,

(...)

• A primeira [parte do governar a lança], por seer mal armado, ou mal corregido do braço da restre, do scudo, da arandella e do gozete;

• Segunda por teer a vara mais pesada que seu poder abrange;

• Terceira, por nom andar assessegado e solto (...).

Quanto ao boo remedio:

Quanto ao primeiro, boo remedio e ensayarse tantas vezes, ataa que nom senta empacho nem torva de cada hũa destas cousas ao tempo que ouver de justar, ainda que per vezes seja ensayado como ja disse, ante que vaa aa tea meta a vara de so o braço duas ou tres vezes, e tenha assy todo corregido que se senta bem senhor della.

Ao segundo, se avyse que ja mais nom traga vara com que nom possa.

Ao terceiro, o assessego e a soltura se ganha per saber da manha e husança della, como ja tenho scripto; e ainda em este caso eu achey, segundo noso custume, de andar atroxados huũ pouco altos, e os atroxamentos folgados, e (...) em razoada maneira nom muyto larga, nem muyto apertada, e que seja bem cavada nas pernas, e corregida de boos coxins e chumaçoos, que nom derree pera detras, nem embroque para diante, fazem os justadores andar quedos, soltos, e bem senhores de sy e de suas varas. (...)

que se doutra guisa aderence poucos podem governar sua lança, e andar aa guisa de boos justadres,ainda que os cavallos que correm rijos, e trazem algũas enxacomas, fazem levar as varas mais assessegadas despois que enrestadas som.»

Capítulo X da V parte:

«(...) os que erram per trigança botarem o corpo e a vara com voontade de encontrar, eso aa segunda voontade que chamey spiritual se pode apropriar. E fazse daquella guisa que alguũs beesteiros com trigança nom podem sofrer o desparar da besta com boo assessego, mes desfecham darrevato ou tisoyrada.

E ainda que conheçam sua myngua, nom se podem emmendar, porque a vontade nom lhes consente.

(...)

Outro sym consiirem quam poucos perigoos dos encontros se recrecem, e como em jugar canas, e monte, e luyta muyto mais acontecem, e que geralmente os homeẽs muyto se despoõem a ello sem receo, e que assy o devem fazer no justar, e tenham voontade de querer ante algũas vezes fazer reveses, ou cayr, que de todo leixar dencontrar. E com tal teençom como esta, se a ryjo teverem , e se qiuserem contynuar, per força he que encontrem.

Por se guardarem do segundo erro, em que disse que alguũns erravam por se apertarem ao tempo dos encontros, se deve teer hũa de tres maneiras:

1. ou levar o justador a vara e o corpo todo seguro e folgado, e nom consentir de fazer nenhũa mudança atee que encontre;

2. ou ante dos encontros huũ pedaço apertar o braço e todo o corpo, tanto que ja quando el chegar nom possa mais, e assy se tenha atee que encontre;

E o 3.º geito he quando alguũs conhecem de sy que nom podem gaanhar cada huũ destes dous, que som os melhores, levamna vara alguũ pouco desviada do justador. E quando cheguarem aos encontros, em apertando o corpo tragam a vara darevato ao encontro, e mais vezes acertaram per esta guisa os que teem geito de se nom poderem teer ao tempo dos encontros que se nom apertem, que de levar a vara dereita aly, onde queriam encontrar, porque apertar do corpo e do braço ao tempo dos encontros lhas fara desvyar.

E do que disse que alguũs erravam por querer de todo encontrar davantagem, desto segundo mynha teençom qualquer razoado justador se deve guardar, mes consiirando sy e aquelc om que justa, e os cavallos e varas que trazem, assy encontre. E se conhecer que tras a vantagem nom recee decer ao scudo; nunca entendo que pode ser boo justador o que algũas vezes nom querer aventurar.

E aalem do suso scripto som de reguardar estes dous avysamentos: